Crime stories weren’t exactly common in Maine. But back in the late 1930s, Public Enemy #1 Al Brady came to Maine to hide out. And he might never have been found had it not been for his longing for the true badge of an American gangster of the time, a Thompson submachine gun. When he tried to pick one up at a Bangor gun shop, the FBI was waiting. He died in a shootout that was so bloody that the Fire Department had to be summoned to wash the blood from Central Street.

By ARTHUR FREDERICK

BANGOR, Maine (UPI) – The stolen eight-cylinder Buick glided to a stop outside Dakin’s Sporting Goods store. Alfred Brady, the FBI’s Public Enemy Number One, slouched in the back seat while another man went in to see if the Thompson submachine gun they had on order had come in.

It was Oct. 12, 1937. Brady’s blood was about to be splashed over Central Street, and the story was about to be splashed across the front pages of newspapers around the world.

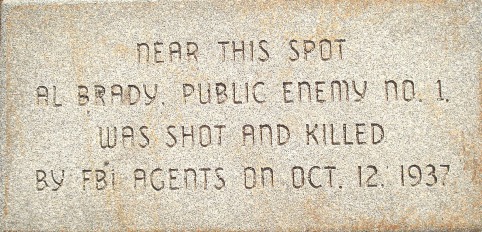

It was the most exciting thing to ever happen in Bangor. Now, 50 years later, the Bangor Daily News hopes to raise enough money to buy a small granite marker to memorialize the gunfight between the Brady Gang and the FBI.

“We’ve put out an appeal to raise $650 for a marker to commemorate the spot,” said Richard Shaw, a Daily News copy editor and amateur history buff who is involved in the project. “So far we have raised about $100, and the readers are really responding.”

The heat was on for the Brady Gang in 1937. Brady and his two henchmen had begun their crime careers in Indiana, and had robbed a string of banks and jewelry stores, killing three people along the way. J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI had launched one of its famous manhunts for the trio, and had named Brady Public Enemy Number One.

The gang found a place to hang out in Connecticut, and began to put together an arsenal.

Brady thought that Maine would be a great place to buy guns. It was fall, and hunting season was about to start. People buying guns shouldn’t raise an eyebrow in Maine, Brady reasoned.

The gang made several trips to Maine in the shiny Buick they had stolen earlier in Baltimore. On one trip they bought a number of handguns, and an obliging merchant at Hussey Hardware in Augusta innocently wrote a letter of introduction to the owner of a hardware store in Bangor when he couldn’t provide the guns the gang had asked for.

Even though Brady had accumulated a number of pistols and rifles, he dreamed about obtaining the true badge of the 1930s gangster, a Thompson submachine gun. When the gang got to Bangor, they went to the hardware store and then to Dakin’s, and Brady asked a clerk about the prospects for obtaining one of the weapons.

The store clerk, Shep Hurd, apparently realized a Thomason submachine gun was not the weapon of choice for most deer hunters. His suspicions aroused, he told Brady he might know where to get a submachine gun, although delivery would take a week.

When the gang members left the store, Hurd went to the police.

Brady and the other two men hung around Bangor for a week, waiting for the gun to arrive. At midday on Oct. 12, they drove back downtown and parked on Central Street near Dakin’s.

The gang didn’t know it, but downtown Bangor was crawling with FBI agents. Hurd, the store clerk, had been replaced by an agent. FBI sharpshooters were at the second floor windows of the buildings across the street. Others were stationed at other strategic spots along the street.

One of the gangsters, James Dalhover, got out of the Buick and entered the store. Brady and Clarence Shaffer Jr. stayed in the car.

Dalhover asked about the Thompson submachine gun and was immediately arrested. Shaffer finally left the car to see what was taking so long, and saw through the window that Dalhover was being handcuffed. He opened fire and was immediately hit with 25 rounds from FBI guns from inside the store and from across the street.

“That was when the FBI opened fire, and hit him with about 25 bullets,” Shaw said. “He twisted around like a top and collapsed in the street.”

The FBI surrounded the Buick and demanded that Brady surrender. Brady had vowed not to be taken alive, and apparently he had meant it; after first pleading with the agents not to shoot, Brady came out of the Buick with guns blazing.

“He got out the driver’s door and started firing at the FBI agents,” Shaw said. “They opened up and loaded him with gunfire.”

Brady and Shaffer died where they fell, spilling so much blood that the Fire Department had to be called to wash down the street. Dalhover was captured and was later extradited to Illinois in connection with one of the gang’s murder. He was later executed.

Shaffer’s body was shipped back to Illinois, but Brady, who had no close relatives, was buried in an unmarked grave at a Bangor cemetery.

Shaw said the paper first planned to buy a marker for the grave, but city officials talked them out of that idea.

“We wanted to mark the grave, it has been unmarked all this time,” Shaw said. “But there are really two reasons for not doing that. One is that people are reluctant to spend money on a headstone for Brady, and the other is to discourage curiosity seekers from going in and maybe stealing the tombstone.”

The marker decided upon would be about one foot by two feet in size, and would be mounted in the sidewalk outside the site of the gunfight.

A number of the contributors have their own memories of the end of the Brady gang.’

“When Al Brady and his gang were gunned down in Bangor on Oct. 12, 1937, John F. Beaton was one of the Bangor firemen who helped clean up the street after the shooting,” wrote one of Beaton’s relatives, Jeanette Beaton. “He has told me the details of that awful job.”

“John is now a patient at Togus Veterans Hospital, but when he was told of the donation campaign to mark Bangor’s part in shooting Public Enemy Number One, he wanted to give, too.”

Beaton was 26 years old when he washed Al Brady’s blood from Central Street. Now 76, Beaton sent along $10.